“Birds and insects, as might have been expected, are very few in number; indeed I believe all the birds have been introduced within late years” – Charles Darwin , Naturalist’s voyage around the world

I ponder if Napoleon went birdwatching during his final years in exile on the volcanic island of St Helena. I mean, what else was there to do really on an island lying far beyond any continental shelf, one of the most isolated places in the world positioned greater than 2000 km (1200 mi) from the nearest major landmass, its only neighbours being the equally isolated islands of Ascension to the north and Tristan de Cunha to the south outside the tropics. If he was by any probability a birder I can imagine his dismay especially after realising that contrary to his anticipation of being banished to America, he was as a substitute sent to an island in the middle of the Atlantic. Because by the time he arrived the islands were already almost treeless and nearly all of the endemic birds were so far as we all know extinct.

Madagascar Fody (Foudia madagascariensis) – One of the many introduced birds on the islands

On July eighth, 1836, the “HMS Beagle” arrived at St Helena only to leave a couple of days later. But that transient visit was good enough for the amateur geologist and naturalist, Charles Darwin, to realise the devastating effect the introduction of latest species had on the native flora and fauna, “ The many imported species must have destroyed some of the native kinds; and it is only on the highest and steepest ridges, that the indigenous Flora is now predominant” (Naturalist’s voyage around the world).

White-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus)

White-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus)

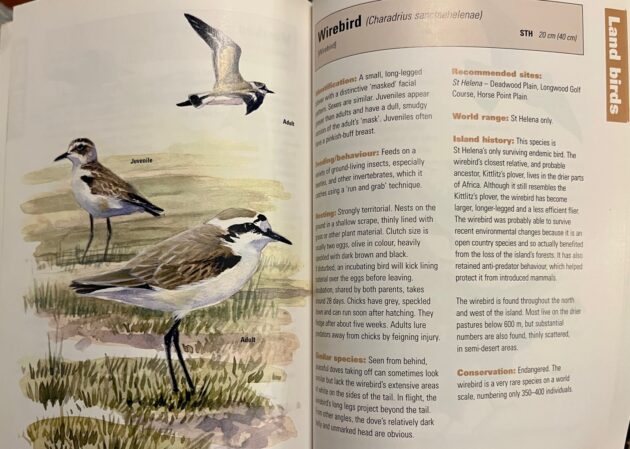

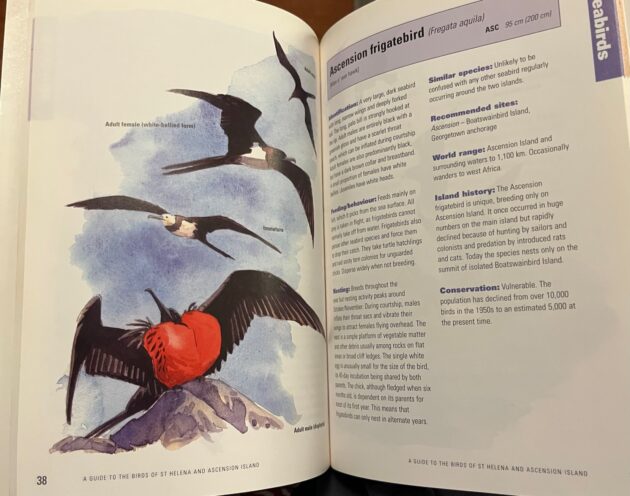

Notwithstanding the undeniable fact that nearly all of the endemics and other native species are extinct the islands of St Helena and Ascension remain highly regarded for birdwatchers and especially photographers because they’re each major breeding sites for seabirds. BirdLife international has designated St. Helena an Important Bird Area due to its abundance of breeding birds comparable to noddies, terns, petrels and tropic birds together with the island’s only remaining endemic bird, the St Helena Plover (Charadrius sanctaehelenae), known also as the ‘Wirebird‘, due to its long, thin, wiry legs. This bird was probably able to survive environmental changes because it is an open country species and so actually benefitted from the loss of the island’s forests. As for Ascension, it also hosts just one endemic species, the Ascension Frigatebird (Frigata aquila), which today nests only on the summit of isolated Boatswainbird Island just offshore.

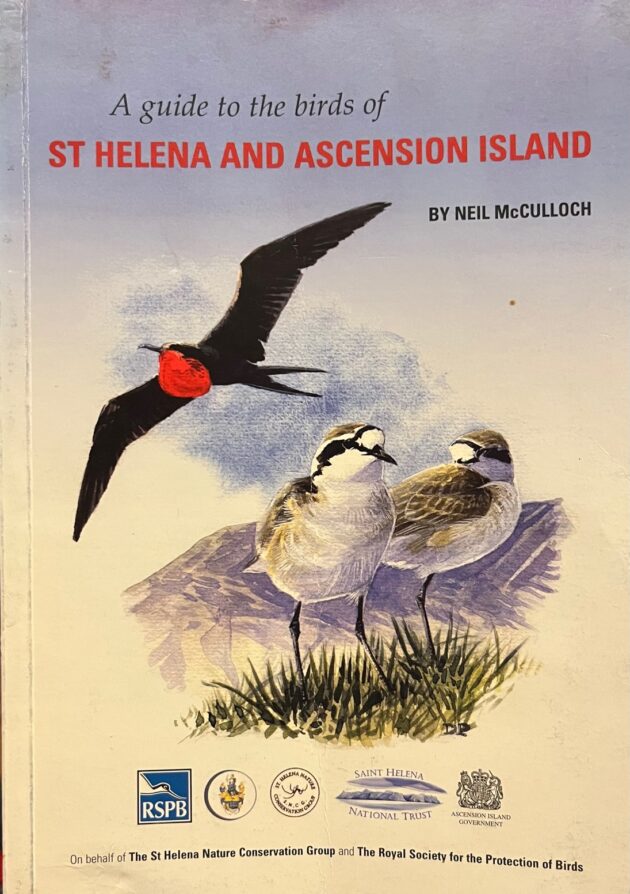

Front cover

Front cover

Now slightly something on the book itself. The layout of the guide is somewhat barely different than what we’re used to. It does follow the general “rule” that places the introduction along with natural history at the starting, followed by the species accounts and ending with a number of appendices. But here’s where this guide is different. First of all, the introductory segment is sort of thorough, covering about twenty pages of a ninety page book. I discovered it to be a really interesting and satisfying read. The creator clearly possesses extensive knowledge of the natural history of each islands. It begins with an outline of island birds basically and how they manage to colonise islands in the first place; then proceeds to narrow it down with describing the natural environments of the islands in query, starting with a historical perspective and ending with the present day situation (which is sort of bleak in my view). At the end of the introduction and before the species accounts there’s inserted a six page description of the best locations where you possibly can see our feathered friends. The locations are numbered and there’s a map of each island present. The species accounts are different in the sense that they’re split into two parts. The first part covers seabirds (petrels, skuas, tropicbirds, noddies, frigate birds, terns and boobies) while the second part describes land birds which apart from one consist entirely of introduced species (the Wirebird is St. Helena’s only surviving endemic land bird). Each species account describes the following: field identification, feeding/behaviour, nesting, similar species, advisable sites where to see the bird and its world range, the species’ history and ecology on the island(s) and the conservation status.

Species account – St Helena Plover or ‘Wirebird’ (Charadrius sanctaehelenae)

Species account – St Helena Plover or ‘Wirebird’ (Charadrius sanctaehelenae)

The plates are large (one species per page so it’s very pleasing to the eye) but the illustrations are somewhat more artistic than what we’re used to seeing in the present popular and renown guides (Helm, Lynx, etc.). At the very end are three short appendices. The first one, and actually for me the most important part of the whole book, describes extinct birds (each endemic and local extinctions). It is devastating to say the least. No lower than 17 species have change into extinct in the past 500 years. How I wish I may very well be in the presence of the probably flightless St. Helena Hoopoe (Upupa antaios), also often called the giant hoopoe for it was 10-20% larger than its African ancestors, but alas that may never occur. The other two appendices cover accidental visitors and failed introductions (of which there are plenty).

Species account – Ascension Frigatebird (Frigata aquila)

Species account – Ascension Frigatebird (Frigata aquila)

This guide is in no way essential, especially today with ebird and what not. It is sort of a rare find and due to its rareness also quite pricey secondhand. If you have already got greater than 10,000 bird species ticked off in your life list and one of the species left for example is the Wirebird and you might be planning a visit to the islands, or should you are a bibliophile and like to have as many bird guides as possible, than this book is certainly for you. So why did I write a review for a guide comparable to this, a guide that only a handful of people would find useful? Because I feel it’s a splendidly written book, for which I congratulate the creator and thank him for giving us a glimpse of St Helena and Ascension.